Introduction

Markets rise, and markets fall. This much, at least, is well-known. But why do market cycles occur? What causes the pendulum to swing from euphoria to crisis and back?

Hyman Minsky was a 20th-century economist whose ‘financial instability hypothesis’ is probably the best-known explanation for the boom and bust cycles that characterize public financial markets. But there’s far less examination — in fact, there's almost none — of how Minsky dynamics apply to private markets.

We’re currently in the midst of an unprecedented boom in private market activity. Tech entrepreneurship, angel investing, and venture capital have never been so widespread. Can Minsky cycles happen in this realm as well?

Let’s find out.

The Inevitable Briefness of Alpha

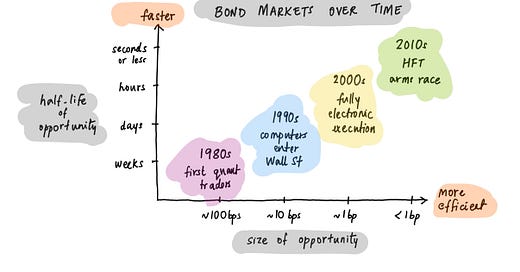

When I started my career as a bond trader at a quant hedge fund, arbitrage opportunities were relatively plentiful. Not many investors had the knowledge or infrastructure to effectively exploit these opportunities, so the early pioneers in the market made good money.

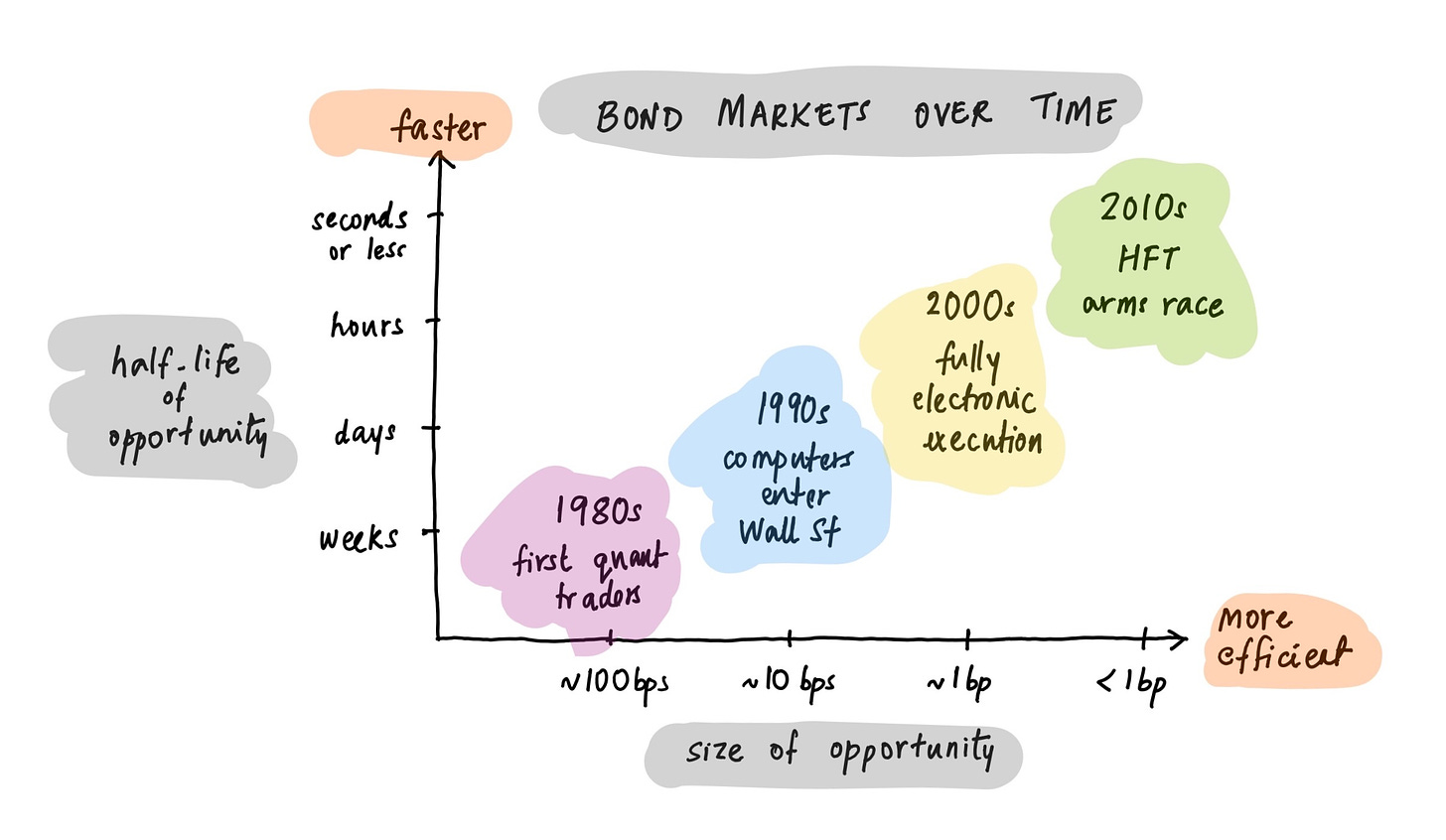

Of course, it didn’t last. Knowledge spreads, technology diffuses, and arbitrages disappear. Markets asymptote towards ever-greater efficiency. This process is extremely well known in capital markets, and even has a name: ‘alpha decay’.

Spreads representing 10s or even 100s of basis points of opportunity, common when I started trading, dwindled to mere 1s of basis points less than a decade later.

… Wait, You Did What?

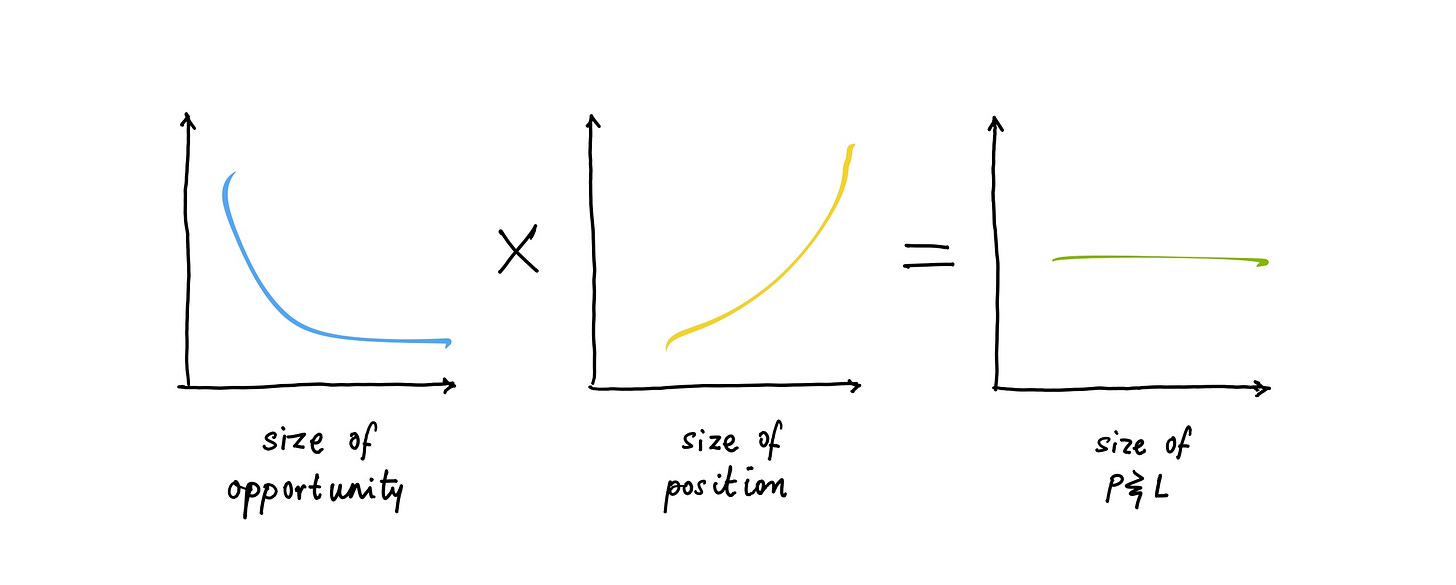

Now, most individuals, when faced with declining opportunities, will reduce their exposure to those opportunities. If a particular strategy made 10% last year but is only expected to make 1% this year, common sense suggests allocating less capital to it.

But institutions … don’t work like that. Trading desks have quarterly P&L targets, and traders have annual bonuses they want to make. There's a widespread culture of “what have you done for me lately?” — you can't coast on past success. The implicit call option embedded in most traders’ compensation profiles exacerbates this.

As a result, faced with a 1/10 reduction in expected value for an opportunity, many institutional portfolio managers will actually 10x their exposure to the opportunity, so as to maintain their dollar P&L. I saw this multiple times in the early 2000s, and it's completely rational, given their incentives.

Mathematics Made Me Do It

But that's not the interesting part. The interesting part is that many risk and compliance models actively encourage investors to do this. Here's how it works.

Most risk models (whether implicit or explicit, quantitative or qualitative) measure the riskiness of a particular investment based on how it and similar investments have behaved in the past. Sounds reasonable, right?

Now, suppose that a particular class of investments, that used to be quite risky in the past, has grown less risky in recent years. A model trained on both historical and recent data would say it’s okay to put more capital to work against these investments than in the past; they’re just not that risky any more. Again, sounds eminently reasonable, right?

“The market is maturing”, is usually how people describe this. Or “The asset class has become more efficient”.

The Illusion Of Safety

Ah, but here's the catch. What if it's precisely the deployment of all this capital that causes the decrease in volatility and hence in perceived risk?

In my own little world of bond arbitrage, spreads were far less volatile in 2006 than in 1999 — because any tiny deviation from ‘fair value’ was quickly met by a flood of arbitrageur dollars pushing the other way. Those dollars simply didn't exist in 1999.

As a result, bond trading in 2006 ‘appeared’ a lot less risky than in 1999. Reward (expected value) declined but risk (realized volatility) declined even more; as a result, Sharpe ratios — roughly speaking, reward divided by risk: a widely used metric of investment performance — went through the roof.

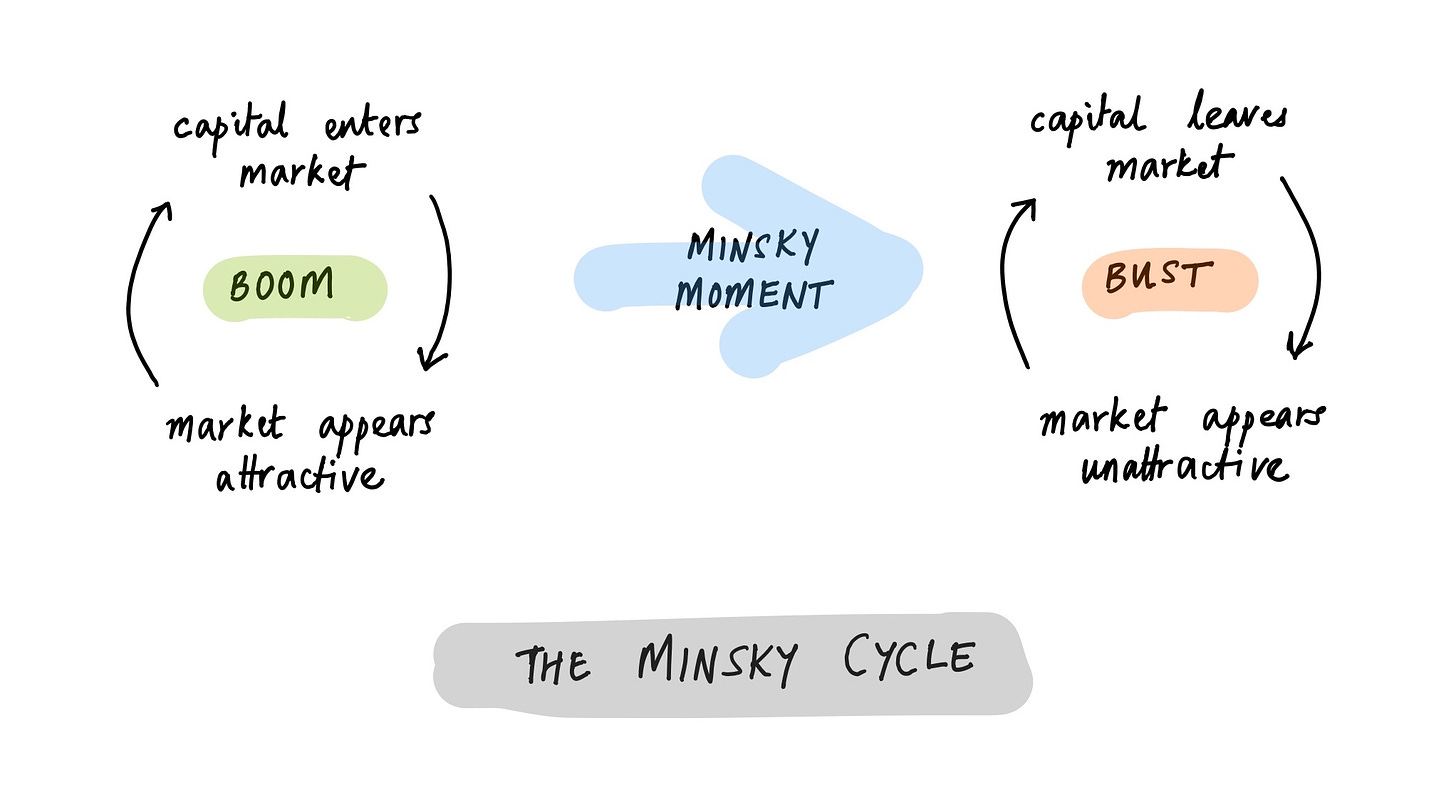

This is the Minsky boom. Money entering a market boosts returns and reduces volatility, leading to very strong (realized) performance. This attracts more money, which improves performance even more. A positive feedback loop ensues.

And this is perfectly legit! Economies can and do reallocate resources all the time. This is how it works; this is how it’s expected to work.

What Goes Up …

The problem with feedback loops is that they tend to overshoot. Minsky booms in an asset class attract a constant influx of new money, but they also need that influx to continue marking up the price and marking down the risk of the asset class. And as the wise man said, “If something cannot go on forever, it won’t”.

Eventually — and fortunes have been made and lost, trying to predict just when that ‘eventually’ comes — something happens. It could be an exogenous shock like COVID, or a tightening Fed, or an election, or a war; it could be an industry-internal event like a particular firm blowing up or winding down. The new money stops, or maybe just slows down a touch, and prices soften. And that triggers all sorts of nasty consequences.

… Must Come Down

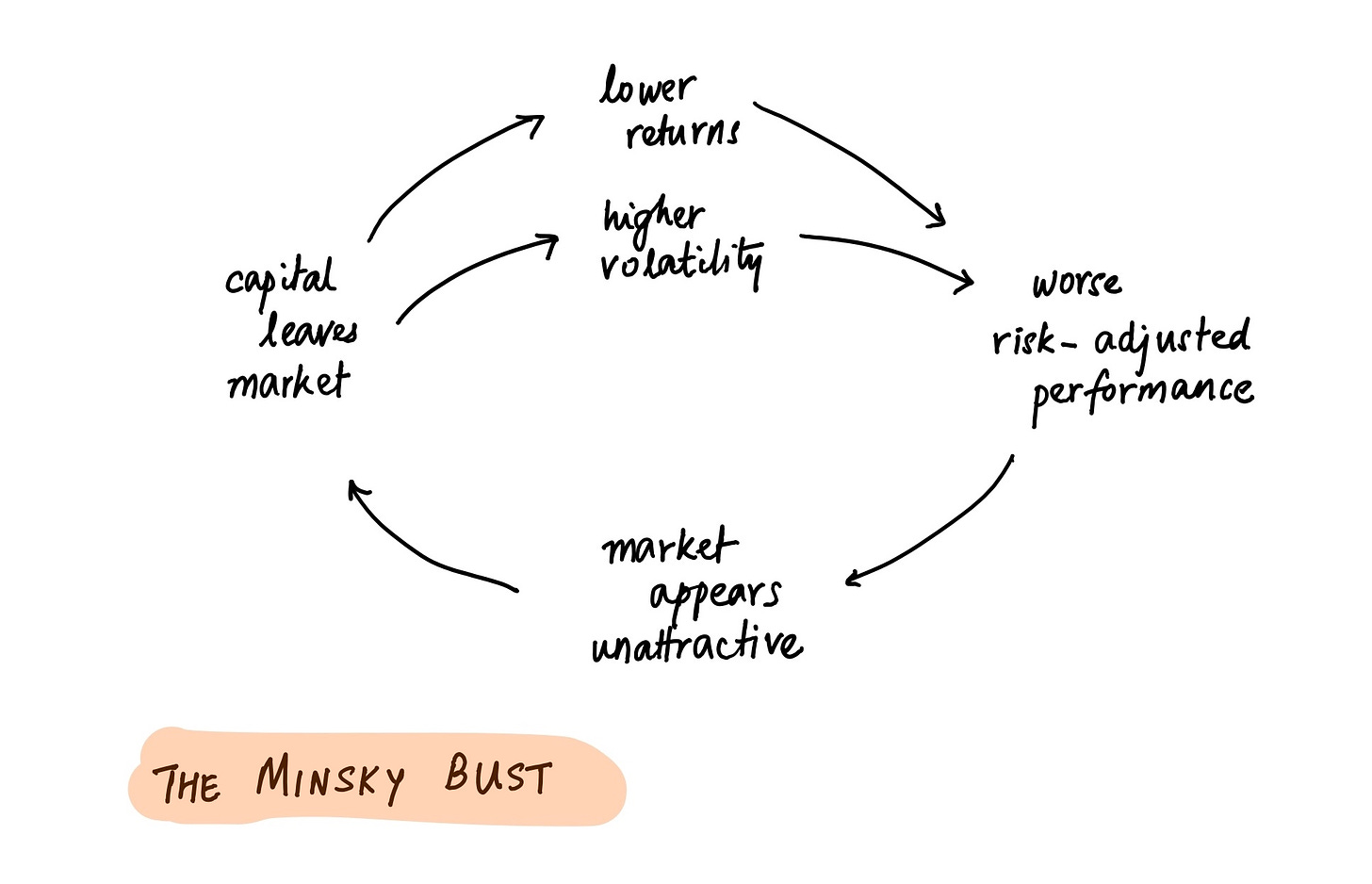

The first thing that happens is that risk-management dashboards start flashing red. Even a slight selloff causes returns to drop and risk to rise; portfolios that seemed well-balanced now appear just a little too aggressive.

Over-extended investors begin to trim their positions. Unfortunately, this causes more price declines, and more volatility, triggering another round of position-trimming. Even conservative investors suddenly realize that their portfolios are riskier than they thought. They sell as well. The ensuing vicious cycle is sometimes called a risk spiral.

Risk spirals are often accompanied by margin spirals. Banks and brokers require leveraged investors to post margins that are proportional to their portfolio risk. As their portfolios become riskier — and remember, the portfolios themselves are often unchanged; all that has changed is the level of volatility in the market — leveraged investors face margin calls. They have to sell assets to service these calls, creating further volatility and downward price pressure; the margin call becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

(That’s why it’s always best to be the first firm to unwind positions or call margin. Goldman — disclosure: Matt Levine used to work there — was very good at this, Lehman less so.)

The final domino is a redemption spiral. Seeing declining performance and increasing volatility, LPs in a fund request their money back. To service these redemption calls, the fund has to sell even more of its positions, triggering yet another feedback loop. Boom quickly turns to bust.

Hello Lehman My Old Friend

This is exactly what happened in credit markets in 2007-08. An influx of cash on the way up, accompanied by the sense that it was a can’t-lose trade; everyone was making money on housing and mortgages and credit. And then an equally unstoppable wave on the way down, as value-at-risk and margin calls and redemption spirals all worked to pull capital out of the credit market.

And Round And Round We Go

In good times, people are encouraged by past success to place larger and larger bets, thinking they're less risky than they actually are, when often it's the very existence of these large bets that drives present success and depresses perceived risk.

Investors believe the trend will continue indefinitely, and become complacent. They invest in lower quality instances of the asset, while increasing their leverage.

And then the music stops. Markdowns lead to deleveraging which lead to more markdowns; the positive feedback loop now operates in the other direction. Eventually, the asset class overshoots as investors become overly risk averse, setting the stage for the next bull market. Stability breeds instability, and vice versa.

Now, all of this is well known. Hyman Minsky fell out of fashion in the 80s and 90s, but his work was rediscovered and widely shared just in time for the GFC. Today it's part of the toolkit for most macro (and many micro) investors; you can also see it in regulatory ideas like market circuit-breakers and systemic backstops.

Is Venture Immune?

But credit is a foreign country; they do things differently there. Let’s talk about early stage tech and venture investing.

At first glance, venture capital seems an unlikely candidate for Minsky dynamics to take hold. Consider:

VCs funds don’t use leverage

They don’t offer redemptions or early liquidity to investors

There are no counter-parties and no margin calls

Volatility is actually good for most VC portfolios (long basket of options)

Without mark-to-market, there’s no chance of a risk-reduction spiral. Without leverage and counter-parties, there’s no chance of a margin spiral. And without investor liquidity, there’s no chance of a redemption spiral. What mechanism could force the liquidation of a venture portfolio, or incept a Minsky bust? For that matter, what’s the mechanism for a Minsky boom in venture?

I Have Confidence … In Confidence Alone

To answer that question, ask this one: where does confidence come from?

The key idea of Minsky cycles isn't that rising prices attract capital; that's just standard trend dynamics. The key Minsky idea is that increasing capital inflows reduce perceived risk.

In the run-up to the GFC, home prices (and much else) went up, but the underlying confidence of the market was rooted in a belief that advances in securitization (everything from Gaussian copulas to CDO-squareds) had delivered genuine structural innovation to the mortgage market, unlocking a swathe of value. And there was prima facie evidence for this belief in the fact that credit spreads were tighter than ever.

Only afterwards did it become clear that those tighter spreads were driven by capital flows into subprime securities, not by an actual reduction in economic risk1.

What's the analogy for venture capital? I suspect that the variable of interest is time.

Fast Is In Fashion

If you talk to almost anyone in venture today, you’ll hear a few themes again and again.

Startups are marked up faster than ever:

Rounds are closed faster than ever:

Funds are deployed faster than ever:

Across every aspect of venture, timelines keep compressing.

In Search of Shortened Time

Timelines in venture have compressed dramatically across the board. This is good news for founders. It’s even better news for investors.

Why so? The superficial answer is IRR. It typically takes 5-10 years for venture investments to generate cash returns. It’s impractical to wait that long, so LPs judge venture firms on their interim IRR. And fast markups dramatically boost IRR.

Firms use these boosted IRRs to aggressively raise new funds, and so they should; if you make 2 and 20 on every dollar you deploy, why deploy slowly? Maximize your lifetime-dollars-deployed.

But there’s a deeper answer. Remember the key Minsky idea: it’s not about returns, it’s about risk.

The ‘classic’ model of venture assumes that startup outcomes follow a power-law distribution: most startups fail, while a small number of outlier successes generate all the upside. Furthermore, “lemons ripen early”: failed startups fail fast — they don’t show the progress required to raise follow-on financing, and quickly go to zero. Meanwhile the outlier successes take time to grow into their full potential. Venture portfolios therefore exhibit a J-curve.

But this is no longer true.

Accelerated markups mean the venture J-curve no longer exists!

Let’s do the math. In the bad old days, if you invested in 10 startups, then 18 months later maybe 3 or 4 would have raised 1 round each of further financing at say a 2x markup, while the remainder would be dead or doomed. Your portfolio as a whole would be worth 0.6-0.8x what you invested: the negative stage of the J-curve. (Note that this is a portfolio that’s doing well!)

Today, if you invest in 10 startups, then 18 months later your 3-4 surviving firms might easily have raised 2-3 more rounds of financing at a 2x markup each time. Thanks to the velocity of financing, your portfolio as a whole could be worth 1.2-2.4x what you invested. Yes, the upper bound is higher, but crucially, so is the lower bound. The fast markups have completely compensated for your lemons! And as a result your risk appears minimal. This is terrific if you’re an investor, and funds know it:

Higher returns and lower risk means new money floods into the sector, accelerating the feedback loop. This is the classic template for a Minsky boom, and it’s all driven by compressed time2.

Many Things Can Be True At The Same Time

Like all Minsky booms, there are some genuine truths underlying the dynamics of the venture market today.

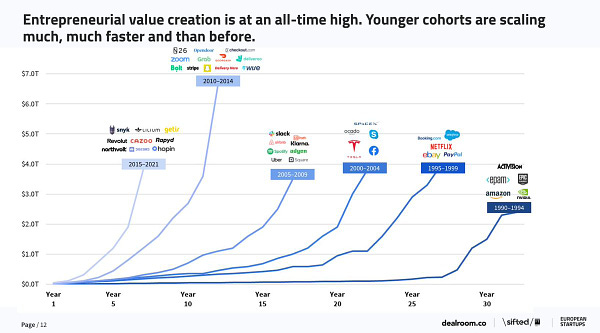

Startups are marked up faster than ever — but startups are also growing faster than ever. 3x year-over-year used to be considered strong; today it’s a bare minimum. The best companies grow at 5x, 10x or even more.

Rounds are closed faster than ever — but it’s easier than ever to evaluate the economics of software companies. SaaS diligence is a solved problem.

Funds are deployed faster than ever — but that’s what maximizes dollars returned, not some arbitrary investment schedule.

Or, in handy graphical form:

These arguments are obviously true. But it was also obviously true (and I’m not being sarcastic here) that there were some genuine structural advances in credit markets in the 2000s, broadening access to loans for borrowers while reducing risk for lenders. This did not stop the credit markets from imploding in 2008.

So are these arguments strong enough for venture to be immune to Minsky dynamics? Is it different this time?

Detour: True Risk and Measured Risk

One way to understand Minsky cycles is that they’re driven by the gap between ‘measured risk’ and ‘true risk’.

When you lend money, the ‘true risk’ you take is that the borrower defaults3. But you can’t know this directly; instead you measure it by proxy, using credit spreads. Credit spreads reflect default probabilities, but they also reflect investor demand for credit products. A subprime credit trading at a tight spread doesn’t necessarily imply that subprime loans have become less risky (though that could be true); the tight spread may also be driven by demand for subprime loans. Measured risk has deviated from true risk.

Similarly, when you invest in a startup, the ‘true risk’ that you take is that the startup fails. But you can’t know this directly; instead you measure it by proxy, using markups. Markups reflect inverse failure probabilities (the higher and faster the markup, the more successful the company, and hence the less likely it is to fail — at least, so one hopes). But markups also reflect investor demand for startup equity. Once again, measured risk has deviated from true risk.

During Minsky booms, measured risks decline. During Minsky busts, measured risks increase. The flip from boom to bust occurs when the market realizes that true risks haven’t gone away.

The Destination, Not The Journey

So now let’s rephrase the question. Has the true risk of venture investments changed? More rigorously:

Does the compression of timelines in venture change the distribution of terminal outcomes for venture-backed companies?

On that question, the jury is still out. It’s not obvious to me that accelerated markups change the power-law dynamics of venture portfolios. Markups change the journey of a business, but do they change the destination?

If the answer is yes, then there’s no Minsky dynamic at play; what we’re seeing is a rational evolution of the venture industry. Maybe startups are truly less risky now; maybe the market truly has matured. More capital, lower returns, safer investments4.

If the answer is no, then venture is very possibly in a Minsky boom, and we’re just waiting for the moment when it turns into a Minsky bust.

What could trigger such a moment?

Reasons For Momentary Lapses

This section is necessarily speculative, but I’ll begin with an observation. There is in fact one well-known death spiral in startup land, and it’s the dreaded down round.

In a down round, a startup running out of cash is forced to raise capital at a lower valuation than its previous financing. This is bad news. Anti-dilution provisions mean that early investors and common shareholders are wiped out. Recent hires whose options are now underwater begin to leave. The startup is perceived as damaged goods, and has to pay above market comp to replace them, attracting mercenaries instead of missionaries. Customers, not knowing if the startup will survive, churn. Finances worsen, predatory investors circle, and further down rounds loom.

A valuation spiral is bad enough. It’s usually accompanied by a talent spiral, which is worse. In a tight labour market, good operators have their choice of where to work. The best startups are able to attract the best talent5. Meanwhile, flailing startups tend to fill up with mediocre employees — the ones who can’t find work elsewhere. This makes it even harder to recruit excellent people 6. The spiral continues.

Down rounds are widely considered the harbinger of doom for venture-backed startups. Understandably, founders and investors go to great lengths to avoid them7.

How do they do this? The most common approach is to wait it out. Cut costs, squeeze out short-term revenue, raise bridge loans from less-known investors at the best terms you can, and hope to eventually ‘grow into your valuation’. Sometimes it even works.

This is — not coincidentally — a perfect mirror image of the logic used by many investors today. “I don’t mind paying up; on the current trajectory, even a doubling in price is easily recouped via just a few months of growth.”

But if my hypothesis about time is true, this could be dangerous. If compressed timelines are the driver of Minsky inflows into venture, then anything that delays funding cycles could precipitate a painful reversal. First some startups delay fund-raising because they need to grow into their valuations; then the VCs who invested in those startups have to delay their own fund-raising with LPs because they don’t have the requisite markups; then the LPs reconsider their (hitherto ever-increasing) allocations to venture because the latest returns are uninspiring; and before you know it, there’s an exodus from the asset class. Minsky giveth, and Minsky taketh away.

Please, Just Tell Me What To Do

It’s conventional to end this sort of essay with some actionable advice. “Here are 5 things that you, gentle founder / investor / operator [choose as applicable] can do, to protect yourself from the coming catastrophe.”

I’m not going to do that. Obvious advice is obvious: while the music plays, it’s best to keep dancing; when the music stops, it’s best to stop. The secret is knowing when the music will stop, and frankly, I have no idea8.

That’s the thing about Minsky moments: they’re easy to identify and dissect in retrospect, close to impossible to forecast in advance. All that we know is this: markets rise, and markets fall. Good luck out there!

Toronto, 12 Feb 2022

Further reading

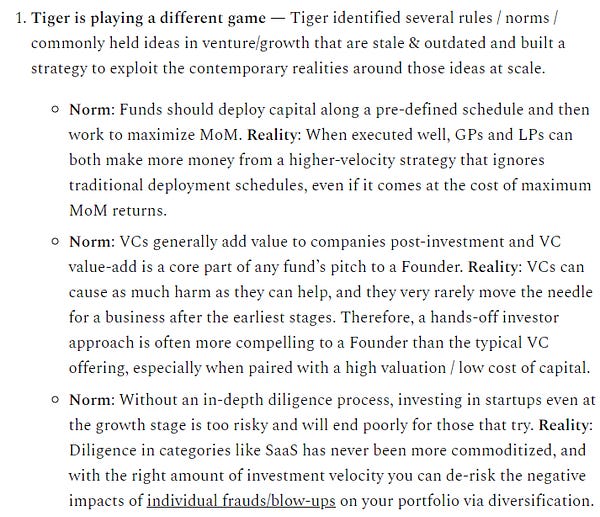

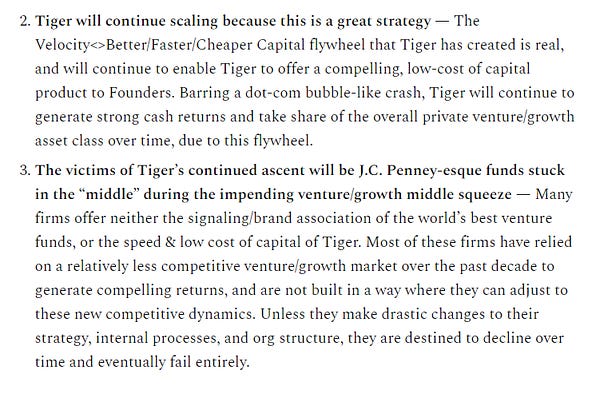

Everett Randle describes how Tiger built “the first structural, non-brand driven competitive advantage and flywheel at scale in venture” — and it’s all based on the effects of accelerated deployment on venture timelines and risk. Possibly my favourite essay of 2021.

I wrote that tech financing doesn’t use debt or leverage, but that’s changing fast. Startups like Pipe have already had great success securitizing software cashflows. Alex Danco predicted this in one of my favourite essays from 2020: Debt is coming.

Byrne Hobart applies the Minsky framework to supply chains, another topic of some current interest. His focus is more on liquidity and leverage than on risk, but the core ideas remain the same.

Housekeeping

I’d like to thank Ruben Schreurs and Venkatesh Rao for their suggestions on style and structure, which helped improve this post substantially.

Thank you for reading! If you liked this post, please do 3 things straight away:

Actually, this is not entirely true. Some credit market participants were aware of these dynamics pre crash, but they were not incentivized to dig too deeply into them.

Why time? I don’t want to get too hand-wavy, but it makes a sort of intuitive sense. If Wall Street is in the business of spatial arbitrage, Silicon Valley is in the business of temporal arbitrage. Wall Street matches creditors and debtors, so the key variable is “spread”; Silicon Valley bridges the present and the future, so the key variable is “time”. Okay, I guess that was a bit hand-wavy.

There are other risks of course: inflation, term structure, pre-payment and so on. But default is strictly bigger than all of those.

An interesting complication here is that startup business models — as distinct from startup equity prices — often exhibit self-fulfilling prophecies: narrative and network effects. But I’m not aware of definitive evidence in favour of what we might call the Softbank thesis — that funding alone can increase win probability sufficiently to justify the higher prices that accompany said funding. So there are wheels within wheels.

Indeed, they’re defined by that ability. The causality runs both ways.

Why does this matter so much? Ultimately, a startup is nothing more than a collection of people, and it succeeds or fails based on what those people do. More mature companies have assets beyond their team; not so early stage startups.

Avoiding potential future down rounds is in fact one of the most cited reasons to not seek overly inflated valuations in the first place, though the number of startups who actually do this is rather small.

“Predictions are hard — especially about the future”.

I've read this 5-6 times since you published this and am surprised by how prescient this was. Elongating time between rounds, higher percentage of down / bridge rounds (source: https://carta.com/blog/state-of-private-markets-q3-2023/), slower fundraising (Tiger's and Insight's botched raises) all happening pretty much as posited.