Making Markets in Time

Silicon Valley and the Invention of Temporal Arbitrage

Three years ago, I wrote a rather successful essay titled Minsky Moments in Venture Capital. I asked: what could cause the boom in venture to roll over into a bust? My timing was spot on: the essay was published at more or less the exact peak of the startup funding bubble, and many of the bubbly dynamics I identified then proceeded to reverse — hard.

One of the themes of that essay was the ‘compression of timelines’ in venture during the boom. Startups were growing faster, rounds were closing faster, funds were being deployed faster. In a footnote, I speculated why time, in particular, should be the variable of interest:

If Wall Street is in the business of spatial arbitrage, Silicon Valley is in the business of temporal arbitrage.

Today I want to unpack that statement, because I think it holds some genuine, and non-obvious, insight. It’s a useful framework to explain what’s happened in venture over the last decade or two, and what we can expect to happen next.

Making Dough from Bread

I bought a sourdough baguette from my neighbourhood bakery this morning. I paid $4 for the privilege.

Why $4? Why not $40, or $0.40? What determines the price of bread?

The list is long. There’s the cost of the ingredients; the value of the baker’s time; regional wages and rents; demand for artisanal baked goods from local essayists; the distance to the nearest supermarket; and so on. These immediate factors in turn are determined by further factors upstream: for example, the cost of flour is a function of the price of wheat, which in turn is a function of sunshine and drought, crop yields and acreage, imports and inventories and substitutes.

It quickly gets complex. But it’s not random. Each part of the bread supply chain is coupled. If wheat prices rise, baguette prices inevitably follow. If consumer demand craters, prices drop. If the proverbial butterfly flaps its wings in Brazil and it leads to a tornado in Texas, guess what: wheat prices react.

But how do these relationships work, exactly? What causal mechanisms link inventory levels at a grain elevator in Saskatchewan to prices at a bakery in Toronto?

It’s commonplace to invoke ‘the magic of markets’ to explain this. But even magic requires magicians. The reality is that these relationships are enforced, by profit-seeking intermediaries. The stage is set for spatial arbitrage.

To Wheat, To Who

Here’s a highly stylized sketch of the wheat/bread supply chain. Wheat is planted, harvested, stored, milled, distributed, baked, and sold. Every stage depends on the stages before and after it. But crucially, no single participant needs to know the full picture in order to be effective.

Imagine I’m Bobby, a baker. I don’t need to know about elevator inventory levels, or fertilizer shortages, or any of that stuff. I set my price based on the price of flour and yeast and salt; my rent and operating costs; my hours worked. If I set it too high, customers will go to my rival Pat’s patisserie down the street; if I set it too low, I’ll go out of business.

Now imagine I’m Dale, a distributor. I don’t need to know about Bobby’s customers or their behaviour; but I do need to know the price of flour from various mills, the demand from various industrial customers, the cost of storage and of trucking. And I’ll preferentially shift my buying and selling and shipping to whatever combination makes the most economic sense for me.

This is spatial arbitrage. Shoppers go where bread is cheapest. Bakers buy from whichever wholesaler is cheapest. Wholesalers and distributors source from where flour is cheapest, and sell where it’s most expensive. If you’ve ever driven a mile out of your way to buy cheaper groceries, then you too, gentle reader, have participated in spatial arbitrage.

The fascinating thing about spatial arbitrage is how it propagates. Participants take actions to maximize their local profits, and these actions transmit ‘fundamentals’ across the economy. If, say, persistent droughts impact the wheat crop in a particular region, its harvest may fall and prices rise; but other producers increase their acreage; distributors reroute their trucks; storage elevators adjust; and eventually a new equilibrium establishes itself, taking into account the new dynamics of supply and demand1.

Futures, Perfected

So this works, and it has worked for centuries; for wheat, and coal, and textiles, and silk, and spices. Local actions lead to global supply chain equilibria.

It works, but it’s not terribly efficient. Rerouting trucks, switching distributors, managing storage levels, planning acreage — there’s friction and effort and uncertainty at each stage, and reaction times are slow.

Enter Wall Street. About 150 years ago, the first wheat futures contracts began to trade. Instead of trading physical wheat, traders could trade pieces of paper that represented wheat, to be delivered on some future date.

These contracts specified two things: what and where.

What: the quantity and quality of grain that is acceptable for delivery.

Where: the location and timing of this delivery.

It may not be obvious, but this simple specification unlocked massive efficiencies in the wheat market.

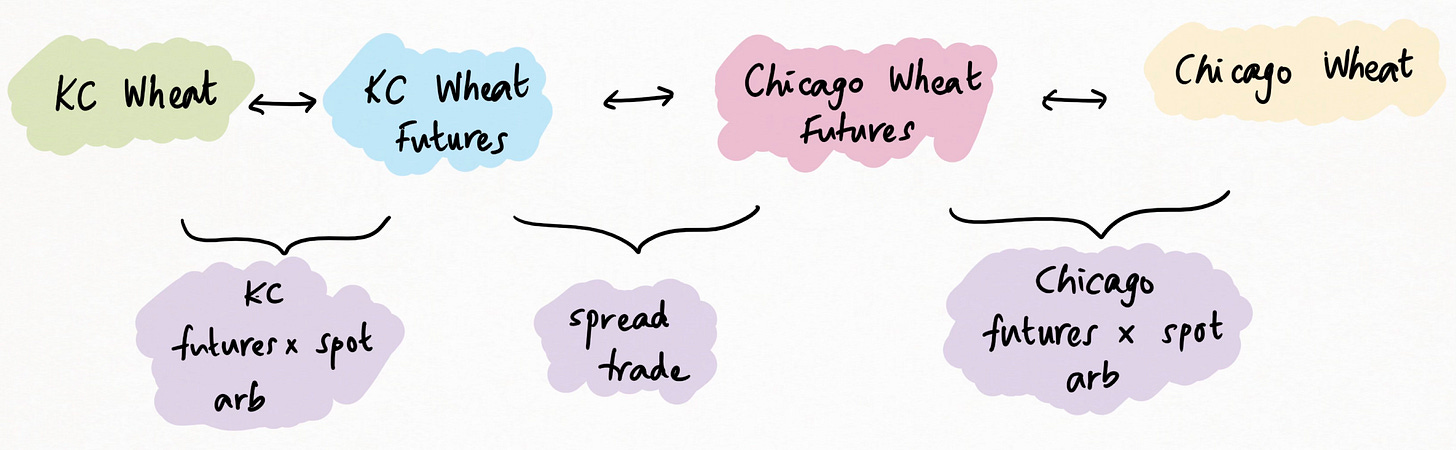

Let’s think about spatial arbitrage again. Let’s say the prices of wheat at Kansas City and Chicago are out of whack: farm prices in KC are $5 per bushel lower than mill prices in Chicago, and it costs only $1 to transport a bushel of wheat from KC to Chicago.

In the bad old world without futures contracts, an arbitrageur would have to buy wheat from a farmer in Kansas City, arrange for it to be transported to Chicago by train or barge or truck, and then sell it to a miller in Chicago. Their actions push KC prices up, and C prices down, until the arbitrage disappears.

This is doable, but it’s complex, and risky, and takes both capital and effort: the arbitrage rewards would have to be quite high to justify such a plan.

Now let’s introduce futures. You can break down the spread between KC wheat and Chicago wheat like this:

And this means you can decompose the trade into sub-trades:

Here’s what happens now:

Kim the Kansas City trader looks only at the spread between physical wheat and wheat futures in Kansas City. If physical wheat gets too cheap relative to wheat futures, they buy physical and deliver it into the futures contract. They may have to hold some inventory, but they don’t care about the price in any other city, or the cost of trucking.

Charlie the Chicago trader does the same thing, in (wait for it) Chicago.

Sam the spread trader doesn’t care about physical prices at all. Instead, they look at the spread between the two cities’ futures contracts. If it rises above the cost of transport between the two cities, they sell the spread and move wheat from one futures delivery hub to the other until it normalizes. They don’t need to interact with farmers or millers or care about initial supply or final demand or the absolute level of wheat prices or anything else; the spread is all that matters.

The beauty of this setup is that you get cross-city spatial arbitrage for free. If farm prices in KC are cheaper than mill prices in Chicago, you no longer need to do an end-to-end trade with all its attendant complexities (and costs). Instead, if each of the intermediary traders does their thing, physical prices at either end of the chain will adjust automatically.

Why is this better?

Each intermediary arb is lower risk, and requires less capital to support

Each arbitrageur can specialize and focus on just one spread

This makes spatial arbitrage easier to execute

And as a result we get tighter markets, faster price discovery, lower volatility, less uncertainty

There’s a shorthand for this: more efficiency. Efficiency is a good thing: it means the economy is allocating resources properly

Efficient markets mean it’s easier for people to participate: farmers, millers, bakers, and ultimately, your humble essayist, clutching his morning baguette.

Divide, Define, and Conquer

Let’s generalize. What’s the structural innovation here?

It’s two-fold: dividing and defining.

Dividing means slicing up the value chain into smaller stages: wheat and flour and baguettes and croutons. And defining means specifying exactly when and where and how the object (product, service) is handed over from one stage to the next: it’s not just wheat, it’s this particular variety of wheat, in this quantity, to be delivered at this place on this date.

And then you financialize all the things: you map these finely divided and carefully defined physical entities to abstract representations (aka securities), and allow people to trade them against each other and against the underlyings.

THIS ONE NEAT TRICK is all you need to supercharge spatial arbitrage.

The Canny Valley

But enough about wheat. Let’s talk about Silicon Valley!

It’s a long road from inception to IPO. As an investor, how do you finance ideas, not knowing if they’ll work? As a founder, how do you get your ideas funded, not knowing how much they’re worth?

There’s a great quote from the classic reference book Numerical Recipes in C:

If the desired X is in between the largest and smallest of the known Xi’s, the problem is called interpolation; if X is outside that range, it is called extrapolation, which is considerably more hazardous (as many former stock-market analysts can attest).

The genius of modern venture capital is that it has figured out a way to convert the extrapolation problem (how do you predict the future of technological innovations?) to an interpolation problem (how do you bridge the gap between idea stage startups and mature public companies?).

And what is this secret, you ask? It’s the same trick that we saw for wheat: divide and define. But instead of slicing and specifying features across space, Silicon Valley does the same for stages across time. Temporal arbitrage!

These stages are called ‘rounds’. These rounds are labelled: angel, seed, Series A, Series B, Series C-D-E-F, and finally IPO or ‘exit’. This is the divide step.

Each round corresponds to some idea of progress in the underlying business. Roughly speaking, Seed is for a team or hypothesis; Series A is for product-market-fit and initial traction, Series B and beyond are for growth and scaleable economics. This is the define step.

What’s more, specialist investors exist to finance each step: to bridge the gap between each stage and the next. Angel investors invest in angel rounds; seed funds invest in seed rounds; and so on2.

And with those simple steps, the full end-to-end financing journey is unlocked.

A seed investor doesn’t have to have a complete analysis of the path to IPO — that’s way too complex, and risky, and uncertain, and unpredictable. All they need to care about is whether the company can plausibly get to the next round. After that it’s the responsibility / decision of the next round’s investor to get to the round after that, and so on.

The comparison to the wheat supply chain is obvious. Kim the Kansas trader doesn’t have to think about trucking costs; that’s Sam the spread-trader’s department. Sam doesn’t have to think about miller demand; that’s Charlie the Chicago trader’s lookout. Ultimately, wheat goes from farm to granary to mill to bakery to supermarket to customer, transforming from grain to flour to bread along the way, but each leg can focus on what it knows (and does best). The analogy is complete.

Efficiency Unlocks Volume

It’s kind of easy to take this for granted, but this is a genuine innovation. It derisks what would otherwise be an impossible sector to underwrite.

More precisely, it identifies, decomposes and then allocates the risks of the sector to people who want to take those exact risks — early stage investors seeking 100x returns on 1 out of every 20 investments and okay with seeing the rest fail, pre-IPO investors seeking 2x returns on all their deals with strong downside protection on the misses, and everyone in between.

This dramatically increases the number of investors who can invest. Less obviously, it also dramatically increases the number who want to invest. In financial markets, diversification is everything; investors flock to whoever can offer them new, uncorrelated, finely-grained sources of risk and return. Supply creates demand, and the invention of stage-based venture financing unlocked a juicy new source of investment supply. Demand — that is, massive capital inflows — followed.

The entire blossoming in venture over the last 15 years has been driven by the maturing of temporal arbitrage. Efficiency unlocks volume. Just as spatial arbitrage ultimately leads to more bread production (better economics, less wastage, more choice, higher quality, specialization and scale effects), temporal arbitrage ultimately leads to more startup creation (for exactly the same list of reasons). To use the terminology of Seeing Like a State, temporal arbitrage made venture legible.

Herd Animal Spirits

Writing about the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in 2023, Matt Levine had an all-time great burn:

I am sorry to be rude, but there is another reason that it is maybe not great to be the Bank of Startups, which is that nobody on Earth is more of a herd animal than Silicon Valley venture capitalists.

But here’s the thing. Given the world that VCs live in — the world of temporal arbitrage — this is a feature, not a bug. VCs must establish strong shared consensus in order for their ecosystem to work.

Why so? Recall that a futures contract specifies two things: the object being transacted, and the location of said transaction. Without these specifications, participants wouldn’t know what to deliver or receive, or where; spatial arbitrage wouldn’t be possible.

Now in the commodities market, these specifications are set by futures exchanges like the CME or the CBOT. But in venture, no such centralized exchanges exist. Instead, the industry as a whole works to create implicit shared knowledge of what and where — or rather, when.

The ‘when’ question is why venture participants are so obsessed with round-specific benchmarks. Product-market-fit! Scalable unit economics! 1M revenue for a Series A and 100M for an IPO3 ! These rules exist to reify the consensus trajectory from inception to exit: they’re not just a roadmap for founders, they’re also a price guide for investors. Inflection points and milestones are more legible than steady compounding.

The ‘what’ question is also why participants talk so much about fundability. It’s not enough to build a good business per se; you need to build a business that is fundable by downstream investors: in other words, that hits the (arbitrary, but consensus) milestones that downstream investors care about.

People poking fun at VCs for being consensus are missing the point. You need alignment on stages and on milestones in order to make the transitions work; and you need support from downstream investors to keep the journey going. Without it, the whole ecosystem comes crashing down, to nobody’s benefit.

Consensus is the Winning Strategy

Common investing wisdom says that to make money, you must be contrarian and right. Venture subverts this. In venture, contrarian/consensus and right/wrong are not orthogonal axes; being right in multi-stage venture is defined by follow-on rounds and markups — in other words, by becoming part of the consensus. Front-running consensus is the winning strategy! Venture is the Keynesian beauty contest in its purest form.

In this framing, a VC’s core competence is knowing when a company is fundable, not just by themselves, but also by downstream investors. Consequently, 80% of the value-add offered by 80% of VCs is helping companies with downstream funding; it’s a goal in itself, not merely a means to an end.

A lot of things now make sense:

the VC preference for in-network and pedigreed founders

the emphasis on self-fulfilling prophecies, in business models and funding rounds

the sense of ‘pre-anointed’ winners (and losers) in the market

the way the entire industry pivots, en masse, into today’s hot sectors, and memory-holes yesterday’s (NFTs, anyone?)

the coded signals and elaborate dance of Bay Area conversations: everyone is trading narratives, all the time

the career risk that a VC takes when investing in an ‘unfundable’ startup (as opposed to a merely unsuccessful one)

the inordinate amount of time that VCs spend talking about round benchmarks, valuations and ‘market’

the backward-induction approach that founders are advised to use when planning budgets and strategy

the difficulty of raising ‘tweener’ rounds, especially at early stage

the disconnect between price, value, and valuation4

the disconnect between startup financial metrics and the financial metrics used by everyone else in the world5

None of this seems obviously a part of ‘find the best companies and give them money’, but here we are.

Movers, Shakers, and Venture Market Makers

Don’t consensus decisions lead to mediocre returns?

Yes, absolutely — and that’s okay! The seemingly illogical and perverse behaviour I just described is merely the price paid for making venture legible, which in turn is what has led to massive capital inflows into the asset class, helping investors and founders alike6. A rising tide lifts all boats; 50th percentile in a booming sector is preferable to 95th percentile in a struggling one7. For the last decade, it’s been totally fine (and extremely lucrative) to be a mediocre VC.

But there’s an even better play here.

Public market investors like mutual funds and hedge funds tend to be price takers: Mister Market sets a price, and the investor chooses whether or not to buy (sell) at that price, depending on whether or not they think the price is cheap (rich) relative to some notion of target or fair or expected value.

VC firms have never been that; startup financing markets are too illiquid, and startups themselves too unique, for there ever to be a ‘market price’. Instead, classic VC firms had to be price makers — setting the price and terms for every deal they printed.

Modern multi-stage VC firms are different again. Modern VC firms are market makers. Yes, they still set terms, and yes, they still want the price to go up. But the consideration of intrinsic or fair value is almost strictly secondary to the question of whether a downstream investor will follow on.

This is market-maker behaviour. Market-makers don’t care (much) about intrinsic value; they care about matching supply and demand. Supply here is founders; demand is (ultimately) public market investors; temporal arbitrage aka multi-stage venture financing enables this large gap to be bridged; and the market-makers take their cut8.

Modern venture exhibits all the classic attributes of market-making:

Consensus, obviously. A market-maker lives and dies by the ability to front-run the crowd; if you’re contrarian, you’re toast.

Price-agnosticism. “You have to play the game on the field” is the purest statement of this attitude; can you imagine Warren Buffett, or any price-taker, saying this?

Coverage. Market-makers care about surface area: they want to see every trade. VCs are exactly the same: dealflow is everything. Top firms religiously measure the number of deals in their mandate that they see (and don’t see) — a metric of zero interest to price takers.

Inventory. You can’t be a market-maker without holding inventory. Hence the proliferation of exploratory and scout cheques from the big firms. The expected returns from these cheques are minimal (if not negative, once you account for non-dollar costs), but collectively they offer optionality on supply.

Correlated books. The big firms are in all the same deals, and they trade with each other incessantly to lay off (but really, merely transfer) risk.

Size-pilling. VCs prefer A- businesses in massive markets to A+ businesses in small ones. Why? Power law math is part of the reason; another part is that large, competitive TAMs mean more dollars deployed. Prop traders hate this; flow traders love it.

Brand. Ever wonder why hedge funds are so secretive about the markets they’re active in, while sell-side banks shout from the rooftops about their position in the league tables? Now observe VC behaviour: do they look more like the former (prop), or the latter (flow)?

Selection. I’m just going to quote @pmarca here: “The core dynamic [that creates scale economies in venture] is that a few firms have positive selection on their side; the other firms have adverse selection working against them”. Every market-maker knows this dynamic in their bones.

Winner’s curse. The higher you bid on a deal, the more likely you are to win it — but there’s a line above which the deal becomes less attractive, no matter how price-agnostic you are.

Franchise protection. Despite adverse selection and winner’s curse, it’s desirable to occasionally print trades that you know you’ll lose money on, because it keeps you in the game. Irrelevancy is the greatest sin.

Winner-takes-all. Market-making is lucrative, but only for the top firms. It’s no good being the 19th largest market-maker — you don’t see enough flow, and you have to pay worse prices; it’s a vicious cycle. Conversely, the top firms benefit from a virtuous cycle of brand, access, capital, pricing power, and returns.

None of this, btw, will come as a surprise to anyone who has spent time on a trading floor9.

The Rise of the Venture Majors

Market-making is simultaneously more lucrative, less risky, and more scaleable than price-taking. As a result, the handful of firms that succeed in capturing market-maker network effects quickly achieve escape velocity. This has led to a new class of player in the industry: the venture majors.

These firms are vertically integrated — they play at every stage, from pre-seed to Series Z. They are horizontally expansive — they play in every sector, from software to robotics to biotech to defence to crypto. And increasingly, they play across geographies, and up and down the capital structure stack. No tech financing event is out of scope for them10.

At the same time, they’re not really hunting alpha. Outperformance is not the point; rather, because of their increasing economies of scale, they just want to be part of every (material) deal. The result is, essentially, beta on the private tech market — it may not be a true ‘index’, but it offers highly-correlated directional exposure to the market as a whole, which is almost the same thing.

LPs love this. Most institutional investors want sector exposure first, and in-sector outperformance second11. The venture majors provide precisely this.

And the incentives don’t stop there. Allocator capital scales better than allocator diligence — it’s so much easier to deploy $20M into one fund than $1M into each of 20 funds. And of course GPs are happy to make 2% of the biggest number possible.

Everybody points to the 2024 statistic that 50% of new LP dollars went to just 9 firms; nobody seems to have a theory of why rational LPs would do this. Market-maker concentration provides the answer!

There’s a clear parallel with history here. Many of today’s largest investment banks — Goldman, JP, Citi — got their start as prop lenders during a previous technological buildout: canals, railroads and coal in the 19th century. They then broadened their franchise into more beta-like businesses like brokerage, depository and market-making — less glamorous, but far more lindy. Prop traders come and go, but banks go on forever.

The goal of the venture majors is to become the investment banks of the technology world. And it certainly looks like they’re succeeding! They say venture doesn’t scale, but this is not venture; it’s a completely different product, with completely different risk-return and investor profiles12.

Ironically, this transition might not be enough! The AI-industrial complex (energy, data centres, compute hardware, training runs, data acq) seems to be full steam ahead on the largest tech buildout ever, and even the venture majors aren’t big enough to finance it; instead the dollars are coming from defense budgets, sovereign wealth funds, and megacap public tech cos (FAANG and friends). The New Deal and Manhattan Project might be better historical analogies — we shall see.

Truly, we live in the most interesting of times!

Toronto, Jan 2025

Notes, Questions, and Further Reading

I use the terms arbitrage, market-making, and spread-trading somewhat interchangeably in this essay. This is not sloppiness or imprecision; rather, it reflects the fact that the boundaries between these actions are blurry, especially when you’re in an illiquid, opaque, discrete market. Normally the pedant (and ex hedge fundie) in me would be up in arms about this; not this time.

It’s a little cringe to cite your own work, but I think my 2022 essay Minsky Moments in Venture Capital remains the best distillation of the dynamics of venture at the height of the bubble. And my predictions around lengthening timescales proved to be very accurate.

One danger with focusing solely on getting to the next round of funding is that it can be gamed. Venture funding can be used to ‘buy’ artifical growth, which in turn can be used to justify the next round of funding, which buys the next round of growth, and so on. You can keep this cycle going for quite a long time, even if the underlying business is a lemon. Paper markups, liquidity from secondaries, and high-profile headlines keep everyone happy along the way. The cynical view is that this enriches founders, VCs, Bay Area landlords, and Google-Facebook-Amazon, all at the expense of LPs. There's probably some truth to that, but note that many LPs are willing accomplices in this game. There are principal-agent problems in every industry.

Two questions I’m currently thinking about. First, what happens if the right anchor of the financing chain becomes permanently untethered, because of a lack of IPOs — can companies stay private forever, and does this increase or decrease the attractiveness of the venture market-making model?

Second, we all saw how ZIRP distorted funding markets. How might future changes in the time value of money — specifically, from AI productivity, or from tariffs and money-printing — affect recurring revenue models and the temporal arbitrage that funds them?

And Finally

A quick word about me: I’m Abraham Thomas, a former portfolio manager at a quant hedge fund, turned successful startup founder (Quandl, acquired by Nasdaq), turned private investor.

Pivotal is my deep-dive newsletter on data, investing, and startups. I write occasional long-form essays on topics where I have meaningful professional expertise: data and data businesses, AI and data, venture capital and angel investing, quant investing in public markets, software startups and business models, and being a tech founder.

If you enjoyed this essay, please take a minute to like, comment, subscribe and share. Thank you for reading!

None of this is new, by the way; Hayek wrote about how price is a mechanism for transmitting information and thus allocating resources over 60 years ago, in a paper that everyone should read.

The tautology is intentional: venture investors are themselves defined by which part of the temporal spread they focus on.

Well, once upon a time, at least.

Venture valuations reflect, not just the current state of the company, but also the probability that it will get to the next (financing) milestone. They’re like bidding conventions in bridge: there’s some correlation with the number of tricks you expect to make, but mostly they’re signals to your counterparty.

VCs love to invent custom metrics that only other VCs use. This makes perfect sense if your primary goal is to sell to those other VCs, in the next round of financing. One of the more hilarious patterns in the industry is how pre-IPO companies hire CFOs who specialize in transforming ‘good startup metrics’ into ‘good public market metrics’.

There’s an analogy here with the maturation of public markets. People like to complain that the relentless investor focus on quarterly earnings prevents public companies from thinking or acting long-term. But it’s precisely the knowledge that public companies are compelled to release accurate, audited, detailed quarterly financial statements (on pain of excommunication from the funding markets), that makes them so accessible to such a large capital base in the first place. 10-K’s and 10-Q’s make public companies legible. Earnings-focused investors are a small price to pay for that privilege.

As many value investors will tell you, through gritted teeth.

“The more the increase in valuation [from the previous round], the more under-valued the company is likely to be.” I forget who tweeted this — someone at A16z, perhaps? — but I remember that it elicited a lot of ridicule from people outside the industry. The statement is, of course, perfectly accurate — if you're playing the game of temporal arbitrage.

Note that market-makers do take prop bets when they think the odds are good. This can work spectacularly — for instance, Sequoia’s multiple rounds of investment in WhatsApp. Or it can backfire — for instance, Sequoia’s multiple rounds of investment in FTX.

Which can often lead to what look like conflicts of interest. It took a hundred years and multiple crises for Wall Street to establish rules about self-dealing, Chinese walls, and inside information; Silicon Valley hasn’t developed those antibodies yet. “No conflict, no interest”, as John Doerr is supposed to have said.

Schmuck insurance. The worst outcome for an LP is to get the macro allocation right but fail to make money because you backed the wrong horse. Back the field instead.

Meanwhile the hunt for alpha moves ever upstream. These days, true venture risk is taken (and venture alpha captured) by funds that don’t fit into the neat, consensus-driven, stage-based financing model that the venture majors sit at the apex of. Instead, they invest in outsider founders, unglamorous markets, immature geographies, hard-to-understand technology, and atypical business models, that often don't even need outside capital.

(Note that many VCs say they invest in these things, but they don’t, not really.)

Thanks for this, Abraham

Market makers need consensus to function, explaining why Valley groupthink isn't a bug but a feature. Though unlike commodity traders, VCs become evangelists for their positions. Maybe because wheat doesn't need storytelling, but the future always does.

I read this multiple times. As much as I appreciate the role of Keynesian Beauty Contest in investments (and life in general), I am unclear on one part - is one of the implications that the early-stage-only firms have no agency on their future? Their role in the value chain is to find cos which late-stage funds will like and to underwrite the risk to the extent of those cos hitting PMF. So their investment strategy is a net reduction of the late-stage funds’ strategy? Would love to know your thoughts here.