The Economics of Data Businesses

How data businesses start, and how they keep going, and growing, and growing.

Data businesses are widely misunderstood

A handful of business models dominate tech today: SaaS, marketplaces, e-commerce, on-demand, social networks and so on. Most of these business models have been studied widely, both their execution and their underlying dynamics.

But there’s one notable exception: data businesses. Despite the fact that many of the largest and most dominant tech firms in the world are data businesses, there are not many resources on the what, how and why of this business model.

This essay is an attempt to change that. Read on!

Definitional aside: What is a data business?

Every company uses data, but not every company is a data business. A company is a data business if, and only if, data is its core product. Data is central to the activity of the company; without the data, there is no company 1.

Google, Bloomberg, Yelp, and ZoomInfo are all data businesses. They acquire their data in different ways, and they generate revenue from that data in different ways. But for all these companies, data is the fundamental unit of value creation.

ONE: It's all about the data

THE FIRST fundamental truth of data business models is this: it’s all about the data.

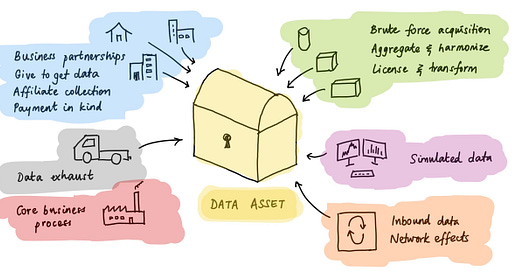

Successful data businesses are all built around a unique or proprietary data asset. There are a few ways to build such an asset:

Brute force: You throw resources at the task of primary data collection. Examples: Google crawling every website in the world; Planet launching 100s of micro-satellites; ZoomInfo cold-calling company switchboards to verify contact info. This is the most common and, despite the expense, often the best way to create a new data asset.

Aggregate and harmonize: You take data that others have collected and published (often for free), and you aggregate, link, and harmonize the data. Example: Reuters standardizing printed financial statements in the 1970s.

License and transform: You license commoditized data and transform it into a value-added form. Example: Scale.AI taking raw images and labelling them at, well, scale.

Affiliate collection: You farm out data acquisition to partners with the right incentives. Example: Advertisers install the Facebook pixel to collect data on customers, which they send to Facebook to optimize their Facebook ads.

Core business output: You create the data as part of your core business process. Example: Every transaction on the New York Stock Exchange generates data (price, volume, orders), which NYSE monetizes.

Payment in kind: You offer a free service or tool, in exchange for data or data tracking. Example: Foursquare’s free SDKs for mobile app developers, which enable Foursquare to track mobile user location.

Inbound network effects: You create a compounding advantage in getting data sources to come to you. Example: Google search is made continually better by site owners submitting data to Google (via SEO and other channels), leading to more Google searches and even stronger incentives for site owners.

Give to get: Partners send you individual pieces of data in order to access the corpus as a whole. Example: Businesses send their counter-party data to Dun & Bradstreet, in order to access D&B’s B2B credit database — which is based on aggregating all these counter-party reports.

(Data consortia are related to give-to-get, but with a peer-to-peer topology instead of hub-and-spoke.)

Data exhaust: You collect or generate data as a by-product of your core business. Example: comparison shopping apps, email managers and personal finance tools all have visibility into consumer transactions; some of them use this to build data products.

Data creation: You generate synthetic data, for applications where ‘real’ data is unnecessary, undesirable, or unachievable. Example: Tonic creates fake data that companies can test their systems on, before deploying to production.

Note that these methods are not mutually exclusive. If anything, they tend to be mutually reinforcing.

TWO: Control unique data to capture unique value

THE SECOND fundamental truth of data business models is this: whoever controls the data, captures the value. Intermediaries get squeezed.

A common failure mode is to build a business on top of somebody else’s data. If you depend on a single upstream source for your data inputs, they can simply raise prices until they capture all of the economics of your product. That’s a losing proposition.

So you should try to build your own primary data asset, or work with multiple upstream providers such that you’re not at the mercy of any single one.

You should also try to add proprietary value of your own, lest either your suppliers or your customers encroach and disintermediate you. A sufficiently large transformation of your source data is tantamount to creating a new data product of your own.

These tactics interact. Sometimes the very act of merging multiple datasets adds substantial value 2. Joining data correctly is hard! Other non-glamorous ways to add value include quality control, labelling and mapping, deduping, provenancing, and imposing data hygiene 3 4.

Some companies, discovering that they can neither control their data assets nor add intermediary value, pivot to picks-and-shovels instead. Tools to support data businesses — everything from monitoring to pipelines to governance — can be lucrative in their own right.

The gold-rush metaphor may be over-used, but it’s still valid. Prospecting is a lottery; picks-and-shovels has the best risk-reward; jewellers make a decent living; and a handful of gold-mine owners become fabulously rich.

THREE: Data business have slow beginnings

THE THIRD fundamental truth of data businesses is this: they start slow.

You’ll that none of the above data acquisition methods are ‘easy’. They need upfront investment or a certain amount of scale to work. Absent either of those, building a data asset is a process of slow bootstrapping.

Adding to the problem is the fact that almost all data products have a ‘minimum viable corpus’ — a size below which the data simply isn't useful. This parallels the concept of a minimum viable product in software, but an MVC is usually much harder to build than an MVP.

The analogy with software doesn’t end there. Almost every apart of the software business stack has an equivalent in the data business stack. Where software firms invest in devops, QA and product, data firms have to invest in data ops, data QA, and data product. These tend to be just as complex, with the extra hurdle that third-party providers are rare, hence you often have to build this infra in-house. All of this is expensive.

As a result, delivering one's first data product requires significant time and resources.

And this is a good thing! Remember the classic wisdom: my capex is your barrier to entry. The effort required to go from zero-to-one in data businesses is one reason they are so formidably defensible. It's also why ‘brute force’ remains one of the most popular strategies used by players in this game. A data product that can be built easily is a data product that can be replicated easily.

But even after you build your data asset, you’re not home free. For reasons we’ll get into later, most data products require category creation. You have to educate your ecosystem, evangelize your product, nurture your customers over time. Early sales cycles are long, and win rates are low. But it gets better — a lot better.

Aside: Nothing ventured, nothing gained

One would think that a business model that requires substantial upfront investment but pays off in buckets later on would be a perfect fit for venture financing. That may have been true in earlier eras, but not today. Tech investing in recent years has indexed heavily on growth rates; as a result, data businesses — with their slow early growth — often find it difficult to raise venture capital.

(It’s also the case that compelling opportunities in data have historically been rarer than opportunities in software, even if they're more lucrative. VCs are familiar with outlier math, but their lack of reps evaluating data businesses tells against them.)

FOUR: Growth accelerates over time

THE FOURTH fundamental truth of data businesses is this: they accelerate.

Everything starts slower on the data side. Building a valuable data asset takes time. Building the supporting infrastructure to actually deliver that data takes time. Sales cycles take time.

The classic mistake people make is to see this and jump to the conclusion that early-stage data businesses don't work and will never work.

But that's a category error, and it’s due to a fundamental difference in dynamics. Software business economics tend to degrade; data business economics tend to improve.

Why so? Here’s how it works:

The marginal cost of acquiring data begins to decline. You begin to see economies of scale on the infrastructure side.

Data sales get easier as your corpus is no longer minimal. Sales cycles shorten, sometimes dramatically.

An expanding corpus also expands your audience: for example, there are many more buyers for data covering 50 US states or 10,000 public stocks than for data covering 10 states or 200 stocks.

You can slice and dice your data for more effective targeting and price discrimination — shortening your sales cycle even more.

As your data becomes widely used, it goes from optional to essential. Customers use it because other customers are using it. The dream of every data asset owner is to become an industry standard. (This doesn’t happen with most other business models).

You can charge more for data. This is partly a corpus-size effect, and partly a table-stakes/must-have effect. Data maturity opens up new axes for pricing — per record, per API call, per data update — in addition to the usual SaaS axes of per use case and per seat.

With more customers, you can amortize your fixed costs of data acquisition and delivery across a wider base — and they’re almost all fixed costs 5.

You can charge recurring revenue; after all, nobody wants to work with obsolete data. (This is harder in the early days, not because of lack of buyer appetite, but because your update cadence probably isn’t good enough.)

The combination of recurring revenue, avenues for upsell, and must-have status means your NRR and LTV are terrific.

You can unlock new channels of data acquisition, most notably customer contribution loops. Models like give-to-get, payment in kind, and affiliate partnerships are now accessible to you. (They weren’t previously, because you were too small to be sufficiently attractive.)

You can also create data quality loops: get customers to not just contribute, but also verify their own as well as third-party data for you, either explicitly or through various behavioural and software hooks.

You can use your data to power your customer acquisition, most notably with a data content loop. Data content loops can be simultaneously cheaper, more scalable and more defensible than most other go-to-market channels, as shown by Expedia, GlassDoor and Zillow.

You can build services on top of your data, creating a data learning loop. As your data improves, these services improve in parallel, growing and contributing even more data to your platform.

Now, many of these effects taper off eventually. Marginal data costs go back up once you start hitting the long tail; price flattens out once the marginal data point no longer adds insight; most real-world entities have finite (even if large) cardinality. These curves are sigmoid, not unbounded.

But you can get a very long way before that happens. At-scale data businesses are huge, and many of them are still growing fast.

The holy grail is when all these scale and network effects combine such that you can be both the lowest-cost acquirer and the highest-paying buyer of your data inputs —while still offering your data outputs to customers at the lowest price in the market. If you get this far, you’re unstoppable.

Case Study: ZoomInfo — from linear to loops

ZoomInfo (NASDAQ:ZI) is a data business whose core asset is a directory — names, titles, contact information — of corporate employees. If you're a salesperson and you want to sell product X to company Y, ZoomInfo will help you identify and contact the exact person Z who you should be talking to.

Here are two fascinating interviews with Henry Schuck, the founder and CEO, conducted a decade apart.

The first one, from 2012, is all about the brute force early stage:

Sramana: Would you talk about the product development process? What were your data sources? How did you put everything together?

Henry Schuck: We were gathering data directly from the companies we were profiling. That is what made our company different back then as well as today. We called into those companies to gather the data and collect the phone numbers, and we updated the information on those people. That is what made all the difference. We did not source data through a crawler.

Sramana: Would you just call the company switchboard and ask for names and numbers?

Henry Schuck: That is basically it. We would start with some online research and identify some top-level people. We would start there and work on building the organization out.

Sramana: It sounds like it was very labor intensive.

Henry Schuck: It was very labor intensive. At first it was just Kirk and me. We were spending 75% of our time on the phone and 25% of our time selling the product. The data was always of paramount importance for what we were doing. As we hired new people, we would split their time to 80% research and 20% sales and marketing.

The second one, from 2021, is all about scale effects:

Jesse: How are you actually getting the data?

Henry: We buy data. We gather data through public sources. We also have two contributory data models. One is we have a freemium model where people can get limited, free access to ZoomInfo in exchange for their email contacts. And so if you ever Google somebody and you see ZoomInfo come up as one of the top results, if you want free access to ZoomInfo, you could [share] your email contacts for that free access. And then we have a customer contributory network. And so a portion of our customers share data with us that we cleanse, validate and send back to them. And we kind of take the exhaust data off of that to help cleanse and manage the datasets. So for example, if you use a marketing automation system, you're going to share bounced data with us and confirmation email data with us. And we're going to use that to cleanse the hundred million records in our system.

If they bounced three times for our marketing automation system, we're going to take those people out and then cleanse the database. And then we have literally a million other unique sources that come in to ZoomInfo. And the thing that sits in the middle of all of that is this evidence-based machine learning algorithm that makes sense of all of the information. You see one person in seven people’s CRMs with different information. You see another person come through eight people's email contacts with different information. And so that machine learning algorithm is consolidating them, connecting them to an individual person and then publishing the most accurate version of that person into the platform.

Every additional customer who contributes, every additional freemium member who contributes, the data just gets better and better and better.

I want to break down all the different loops and motions in play here:

Give-to-get / payment-in-kind: Users get free access to ZoomInfo's ‘Community Edition’ by giving ZI access to their own email contacts.

Affiliate contribution network: Customers send raw data to ZoomInfo; ZI returns cleansed, validated data, and also keeps some of it for themselves.

Data quality loop: ZoomInfo collects duplicate profiles from dozens of sources, and runs ML to infer the ‘most accurate’ version of each profile. The more sources, the more accuracy; and accuracy is a major selling point for ZI.

Data exhaust loop: ZoomInfo uses customer exhaust data — for instance, email confirmations and bounces from marketing campaigns — to update and improve their own database.

Data content loop: A big source of ZI's leads is SEO: when you search for a person, their ZoomInfo profile is often on page 1 of the results. The more profiles, the more leads; the more leads, the more profiles (thanks to the acquisition loops above).

And all of this pays off:

Accelerating go-to-market: As the data gets bigger and better, it gets ever easier to sell. From the transcript:

Henry: It’s just hard not to see how much value you get out of that the first day you turn it on.

Jesse: Right. I’m sure their head explodes.

Henry: Yeah. Their head explodes.

Jesse: They become very skeptical. Then you go, “Go drive to the address and you can verify my data.”

Henry: You can validate the data. Tell us the company you’ve sold to over the last couple of months, we’ll just show you them inside of ZoomInfo.

...

Henry: Our average sales cycles are sub-30 days ... There are dozens of deals every month that we sell same-day.

Multi-axis pricing: ZI can offer per-seat, per-record, and per-use-case (sales, marketing, recruiting) pricing, depending on the client.

Brute force at scale: ZI has a data verification team of 100s of people, and crawls ~40M websites daily for profile updates.

Exceptional economics: ZI’s margins grew from 50% in 2014 to 90% at the time of this interview. NRR is above 100% and accelerating. The go-to-market motion has a 6-8 month payback period and 15:1 LTV/CAC. That's not a typo.

Note that ZoomInfo did not raise venture financing; they were bootstrapped until a private equity round in 2014.

FIVE: Data businesses are super sticky

THE FIFTH fundamental truth of data businesses is this: they are virtually impossible to displace.

I’ve talked about this before 6:

The conventional wisdom in tech is that customers will switch to a new product if it’s 10x better than what they're currently using.

But what does ‘better’ mean for data?

If your data product is substantially similar to existing products, then one way to be ‘better’ is to offer a dramatically lower price. But this doesn’t work for data! The concept of minimum viable corpus means you need to be above a certain size and quality, else your data is almost worthless. And the very particular economics of data acquisition (brute force, economies of scale, data collection loops) mean that it's hard to build an MVC that’s dramatically cheaper than the incumbent offering. So ‘disruption from below’ rarely works.

Another option for being ‘better’ is to go the other way — offer dramatically higher quality. Typically, you need to be an order of magnitude faster, or more accurate, or more comprehensive — sometimes all three! — before you start poaching customers from the incumbents.

And even that might not suffice; the value of data lies in what can be done with it, and often, increasing speed or accuracy or comprehensiveness doesn’t really increase utility by enough. If you're competing with a table-stakes data product, heck, even increasing the utility by a huge amount won't work.

One way to think about this is in a ‘jobs-to-be-done’ framework. If a particular piece of software does a particular job, it's relatively easy to imagine a next-gen product doing that same job 10x faster or better or cheaper. But it's actually quite hard to envisage what an improved version of an existing data product can do that is 10x better than the existing data product.

In fact, typically, a successful new data product is not a variation on the existing data; it’s a brand new data asset from a completely different source, exploiting a completely different set of loops.

Meanwhile the original data asset continues to sell. Churn rates for mature data products are minuscule. So just as a matter of usage, it’s quite difficult to disrupt established data businesses.

Then there are all the ‘classic’ sources of defensibility mentioned previously: high barriers to entry; economies of scale in data acquisition and infrastructure; positive feedback loops / network effects in data and customer acquisition.

And finally, incumbents can use certain tactics to bolster their structural advantages:

‘Commoditize the complement’ is the best known — either with software, or with third-party data 7.

‘Creating data standards’ is another common one — every large data business has done this, from PCI to CUSIP.

‘If you can’t beat them, buy them’ — mature data businesses are extremely acquisitive. If they can buy data that is either additive or adjacent to their core product, they almost always will.

Put it all together, and mature data business have a set of flywheels and compounding structural advantages that are almost impossible to displace:

But data businesses aren’t quite winner-takes-all. Instead, the biggest ones tend to form duopolies — think Visa and Mastercard, Nasdaq and NYSE, Google and Facebook, Moody’s and S&P, Experian and Equifax, Bloomberg and Refinitiv. I suspect this has more to do with de facto government policy than with actual business dynamics.

Aside: 180 years, 4 presidents

Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, Grover Cleveland and William McKinley all worked for the same data company: Dun & Bradstreet.

Dun & Bradstreet (NYSE:DNB) is 180 years old. No business survives that long (two world wars and a civil war, recessions and depressions, market booms and busts, multiple technological revolutions, good and bad management, you name it) without an amazing structural moat. That’s the power of data businesses.

And DNB is far from the only centenarian data business in the world! Equifax was founded in 1899. Reuters was founded in 1851. Various Lloyd’s entities (the List, the Register, and the insurance mutual) were founded between 1686 and 1760. Standard & Poor’s dates back to 1860. All data businesses, all chugging along today, and none of them particularly close to being disrupted.

In SaaS a particular generation of software can become obsolete in a few years; products built in the early 2010s look decidedly old in the tooth today 8. But data businesses can last for decades, and as the above examples show, even centuries. Invest in building a data asset once, keep customers forever: the ratio of LTV to product creation costs is off the charts.

SIX: Successful data businesses are rare

THE SIXTH fundamental truth of data businesses is this: they are rare.

You might think that starting, buying or investing in data businesses is a slam dunk. Unfortunately, it’s not — and that’s because successful data businesses are rare.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise, because valuable data is also rare. There's a lot of data in the world, but most of it is junk. (Sturgeon’s law: 99% of everything is junk). The list of criteria that a data asset must meet in order to be the core of a successful data business is long and extremely restrictive.

And of course, many ‘obviously valuable’ data assets (information about companies, say, or people) have already been captured. That leaves non-obvious data assets9 — which in turn implies category creation. Category creation is hard!

But (speculation alert!) I wonder if we might see a ‘deployment era’ for data just like we’re currently seeing in software. Instead of massive horizontal platforms covering entire information categories like people, companies, or events, I wonder if more targeted, bespoke, vertical- or application-focused data businesses will emerge — data for very specific niches. We shall see!

Toronto, 29 Jan 2022.

Further reading

Kevin Kwok has a great essay on data content loops. This was a strategy we used to great effect at Quandl, the data business I co-founded. Kevin describes how Rich Barton used it thrice, at Expedia, Glassdoor and Zillow.

Auren Hoffman has a terrific and comprehensive Data-as-a-service Bible. I also recommend his World of DaaS podcast, especially his interviews with other data business founders.

I wish there were an essay with a truly in-depth treatment of Google as a data company (which it so clearly is!), not a search or advertising or content or AI company. If you come across such an essay, I'd love to read it.

Housekeeping

This is my very first Substack post; thank you sincerely for reading this far! If you have any comments or suggestions, please send them in.

If you liked this post, please do 3 things straight away:

People sometimes use ‘data business’ and ‘data-as-a-service’ interchangeably, but strictly speaking DaaS is just one flavour of data business; there are many more.

“ZoomInfo’s core offering is a primary key for the database of every employee at every US company.” — Byrne Hobart

Note that merely ‘repackaging’ data is rarely sufficient to generate strong economics. This is another common failure mode: thinking that dashboards and visualizations and interfaces are the key to a data business. Data consumption UX is a nice-to-have; data itself is the must-have.

Data brokers exist; they benefit from marketplace magnetism, and the best ones offer a lot more than mere match-making.

Apart from a few very large or very fast datasets, data delivery has fairly low marginal costs.

Though I mischaracterized it as an enterprise SaaS business. The Bloomberg Terminal is actually a SaaS application built on top of a data business.

Google, creator of some of the most powerful software in existence, is happy to open-source large chunks of their code, but they keep a tight rein on their data. I find this revealing.

Some of the most moat-y SaaS companies are the ones that have created a data asset: Salesforce's role as the system of record for most of its clients is perhaps the best example.

For example, who would have thought 20 years ago that ‘intent’ was one of the most valuable assets in the world?