One of the wisest and most important pieces of advice I received as a startup founder was this: “The worst outcome is a mediocre success”.

Now, this is not a simplistic exhortation to go big or go home, hit a home run or strike out, be blindly ambitious, any of those things. It's subtler than that. Let me explain.

Startups are defined by uncertainty. As a founder, you have to discover almost everything about your business: What is the product? Who are your customers? How will you reach them? How much will they pay? Who are your competitors? How is the industry evolving? The list goes on.

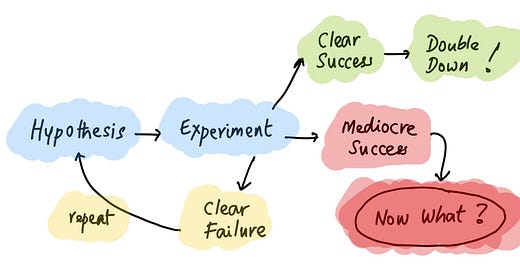

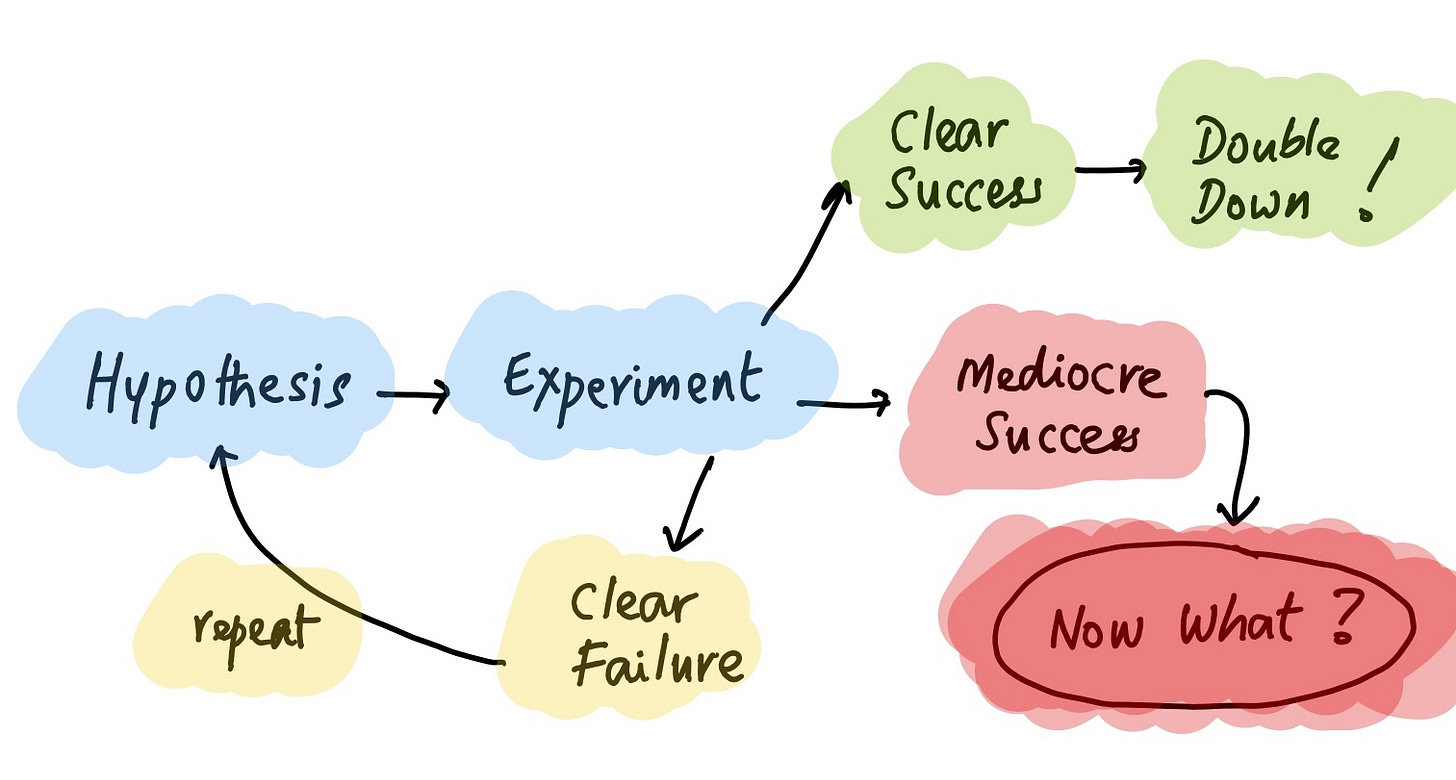

One common way to answer these questions is, essentially, the scientific method, applied to tech startups. Frame a hypothesis; run an experiment to test the hypothesis; confirm or disprove the hypothesis; learn and iterate and learn and iterate.

For example, your hypothesis could be that ‘Cold-calling customers will lead to sales’. So you hire a couple of sales reps and tell them to cold-call 100 customers. If you get 30 new sales out of that (a terrific hit rate) — great, the hypothesis is true! You can hire more sales reps and double down on this tactic. And if you get 0 new sales — that’s also great, the hypothesis is false! You can move on to other acquisition tactics like FB ads or SEO or events or whatever. Either way, your experiment worked in confirming or disproving the hypothesis.

The worst outcome, the very worst outcome, is to get a small but non-zero number of sales — say 1 or 2. Because now you're in a bind. Do you double down or pull the plug? Does cold-calling work or not? Could it be that the method works, but the sales reps aren’t hustling enough, or they’re not following the right script, or they’re not calling the right people? Or maybe the method is flawed and your reps just got lucky? You just don't know!

That’s the danger of the mediocre success. The point of startup experimentation isn't the success itself; it’s the learning that comes with clear-cut success or failure. You don't really care about the sales revenue generated by your first two reps; you care about whether this is a strategy you can scale to dozens and then hundreds of reps, or whether you need to use a completely different strategy. It’s all about the learning. And mediocre successes don’t give you any learning.

Unfortunately, there’s a natural human tendency to hedge our bets — to make design choices in our experiments such that a mediocre success is the most likely outcome. There’s also a tendency to only do experiments that you know in advance will work — but such experiments are not useful: the delta in information is close to zero. For example, and continuing the sales experiment: as a founder, you could do the calls yourself; reach out only to the very best, most qualified prospects; create custom collateral; offer sweetheart pricing. All those actions will increase the chances of closing any one deal, and as a result they’re very tempting, but do they tell you if cold-calling is a viable sales strategy at scale? Nope.

Making it worse is that we’re all heavily socialized to aim for mediocre success. Schools, universities, large organizations — they don’t want big swings and big misses; they want safety and consistency. A steady 7 is better than 10s interspersed with 0s. This might work well in structured, predictable environments, but in startup-land it’s anathema.

So when a startup comes to me with an idea for an experiment, the one thing I tell them is: make sure that there’s a well-defined distinction between success and failure. Don't fall in the messy middle. If the hypothesis fails, make sure it fails clearly and unambiguously; if it succeeds, make sure it succeeds equally clearly and unambiguously. And remember that a hypothesis failing means the experiment succeeded; you learned something. That’s what it's all about.

The worst outcome is a mediocre success!

Toronto, Sep 2023.

End Notes

This essay is about tactics, and specifically about how mediocre successes hamper your learning. There’s a whole separate essay to be written about mediocre success in the realm of strategy, which is largely about opportunity cost.

I’m experimenting with the content and form factor of this newsletter. In addition to the long-form, deep-dive pieces that I’ve written so far, I’m going to write some shorter single-topic pieces like this one, hopefully at a higher cadence. I’ll also widen the scope to include more personal anecdotes, tactical nuggets and random riffs. Let’s see how it goes!

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe, and share it with 2-3 other folks who you think might enjoy it as well. I’d like to get more subscribers, and Twitter/X is no longer the reader-content discovery engine it once was.

First time reading your work, was linked her from The Diff, by Bryne Hobert.

As I read this I thought of the old sport axiom of basketball... You never want to be mediocre. You want to bottom out for draft picks, or go for the title. Going for the middle is death.

Teams in the middle, are expensive, and won't win. You never learn anything from them.

To expand the analogy, better to lose OFTEN with young, high upside players (learn, iterate)

than middle along with known players with no room to improve - (mediocre success)

A lot of what you say applies to science too, nice stuff Thomas :-)